The history of Rome’s Università dei Marmorari

From its inception to nowadays

In the Roman imperial period, white and coloured marbles, coming from quarries located in all the known world at that time, started to be greatly used and appreciated. Those colourful marbles were used to decorate big public buildings, palaces, sumptuous imperial villas, and city and countryside houses of important senatorial families and of wealthy Roman freedmen.

In the Roman imperial period, white and coloured marbles, coming from quarries located in all the known world at that time, started to be greatly used and appreciated. Those colourful marbles were used to decorate big public buildings, palaces, sumptuous imperial villas, and city and countryside houses of important senatorial families and of wealthy Roman freedmen.

The passion for white and coloured marble used as a decoration for houses, villas, and temples did not start in ancient Rome, but it’s in that period that marble reached the height of its glory. As a matter of fact in ancient times, marble was considered a luxury material to be used almost only for big public buildings, palaces, sumptuous imperial villas, and for city and countryside houses of important senatorial families and wealthy Roman freedmen.

After the decline of the Roman Empire, Rome’s magnificence faded away. There came centuries of sacks, lootings, and marble reutilisations. The habit of reusing coloured stone materials continued during the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and the Mannerism period, and then it revived during the Baroque and Rococo periods in many parts of Italy. In the Middle Ages, the Roman Marmorari (Roman dialect for ‘marble workers’) were the ones who mastered the art of reusing marble. Their art movement started in the XI century and was inspired to the great traditions of ancient Rome.

Among those artists there were not only marble workers but also rough hewers, stone carvers, stone decorators, stonecutters, sculptors, stonemasons, and mosaicists. Marmorari are best known as Cosmati, for some of these craftsmen’s families had the name Cosma. Nevertheless, for stylistic similarities, the name was given also to other masters and families, like the Vassalletto family.

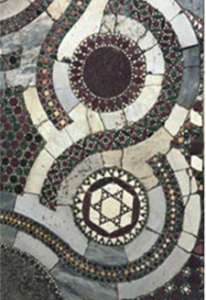

As a matter of fact, their “Cosmatesque” creations reflected the art of opus sectile, an inlay stonework of geometric shapes (rectangles, squares, triangles, hexagons), spirals, and interlacements which gives birth to magnificent polychromatic works of art. Rome’s Marmorari used their art to make Roman basilicas shine again, through the decoration of ciboria, pulpits, bishop’s thrones, choirs, porticos, bell towers, and floors. From Late Antiquity to the early XX century, the marmorari had Imperial Rome’s monuments and excavations as a huge open air quarry full of all the coloured marbles coming from every province of the Empire.

One of the many Italian examples of transportation of old stone from Rome is the reconstruction of the Abbey of Monte Cassino in the Middle Ages (1006-71), under the regency of Abbot Desiderius. Desiderius called in specialised workers from as far as Constantinople to carry out the mosaics and work all the marbles; as a matter of fact, Cosmatesque works were highly influenced by Bizantine art, which melted with the stronger traditions of Imperial and early Christian Rome.

Rome’s Marmorari: tradition and renewal

Between the XII and XIII century, Rome’s architectural look was refreshed, for early Christian Roman basilicas (IV century BCE) were taken as models. The habit of reusing marbles and of using old techniques, like opus sectile or the one for realising Roman wall and floor mosaics, didn’t stop. This renewal of Rome happened at the time of the reformation of the Catholic Church (Investiture Controversy) promoted by Pope Gregory VII (1073-1085). The Church was corrupt, decadent, and neglected. After the Gregorian reformation some basilicas were renovated and decorated; that’s why towards the end of the XII century, with more power in the hands of the Pope, a larger use of coloured stones in the basilicas can be noticed. The marmorari were able to revise the ancient models they used as a reference by adding some new elements which fitted the style of the age they were in. One of the new architectural elements was the belfry. Evidences of marmorari’s art are also the wonderful cloisters.

Between the XII and XIII century, Rome’s architectural look was refreshed, for early Christian Roman basilicas (IV century BCE) were taken as models. The habit of reusing marbles and of using old techniques, like opus sectile or the one for realising Roman wall and floor mosaics, didn’t stop. This renewal of Rome happened at the time of the reformation of the Catholic Church (Investiture Controversy) promoted by Pope Gregory VII (1073-1085). The Church was corrupt, decadent, and neglected. After the Gregorian reformation some basilicas were renovated and decorated; that’s why towards the end of the XII century, with more power in the hands of the Pope, a larger use of coloured stones in the basilicas can be noticed. The marmorari were able to revise the ancient models they used as a reference by adding some new elements which fitted the style of the age they were in. One of the new architectural elements was the belfry. Evidences of marmorari’s art are also the wonderful cloisters.

Revival of ancient times: shattering of the Roman opus sectile in Medieval times

The renewal of Rome happened together with the progressive shattering of ancient marbles and architectural pieces. Many very old buildings had already been demolished or stripped of their fine stones, for using again coloured marbles, after their transformation in shape and thickness, was a common practice in the Late Antiquity. Rome’s Marmorari, by continuing the tradition of despoiling marbles and shattering them into pieces, invented a new mosaic style, geometrically versatile but very vivid and colourful at the same time. Since the VIII century, only the Pope had the right to authorise the despoliation of old buildings to be used as marble quarries, but later on, between the XII and XIII century, some families got that exclusive right.

The inside of Rome’s basilicas, with their liturgical furnishings and splendid floors, were the main proof of this revival of ancient styles. Materials were taken from ancient ruined buildings; by sawing broken red porphyry columns, perfect circles were obtained, the so-called rotae, which, with the passing of centuries, shrank in diameter. Due to lack of materials, in the last years of Cosmatesque production, those big porphyry circles became just a composition of fragments.

The inside of Rome’s basilicas, with their liturgical furnishings and splendid floors, were the main proof of this revival of ancient styles. Materials were taken from ancient ruined buildings; by sawing broken red porphyry columns, perfect circles were obtained, the so-called rotae, which, with the passing of centuries, shrank in diameter. Due to lack of materials, in the last years of Cosmatesque production, those big porphyry circles became just a composition of fragments.

Shattered slabs became tesserae for mosaics or just shapes to create geometric composition with. Many shattered marbles were used for new constructions or turned into lime; marbles were commonly taken from the ancient tubs located in the many private and public Roman thermal baths. Those tubs were either turned into fountains or, especially, used to place the mortal remains of saints and martyrs and as basements for famous altars.

It’s worth noting that in the XII century those marble workers’ workshops realised brand new Ionic capitals, which soon replaced despoiled capitals, thanks to their being very similar to one another and easy to adapt to the diameter of the columns. The Cosmatesque activity came to a stop in the early XIV century, with the Avignon Papacy.

That is proof of the strong connection between the Catholic Church and the activity of Rome’s Marmorari. When the papacy was restored to Rome, times had changed and marmorari’s activity was not the same as before, as can be seen with the struggles suffered by their corporation.

Main figures: families, workshops, and artists

The peculiar way of working marble by marmorari’s families and workshops is characterised by the same composition and decoration patterns. Differences in styles are then revealed just by tiny details.

The most ancient Roman Marmoraro is Christianus magister. His name is engraved on what remains of Cardinal Peter’s grave in the Basilica of Saint Praxedes (about 964 CE).

The Basilica of San Clemente is one of the rare examples where the complex liturgical furnishing decorated by the marmorari is almost untouched. The original basilica (358 CE) was rebuilt in 1108 under Pope Paschal II. The entire longitudinal axis of the nave is marked by porphyry rotae bound together. Between the entrance and the choir, a second aisle with circular elements intersects the nave. Once there was a bigger central pattern right in the intersection. For example, the floor of Saint Peter’s nave features a big porphyry rota, where a cardinal and the future emperor prayed during the emperor’s coronation. The choir is enclosed with marble plutei from the lower church dating back to the age of Pope John II (533-535 CE).

The Basilica of San Clemente is one of the rare examples where the complex liturgical furnishing decorated by the marmorari is almost untouched. The original basilica (358 CE) was rebuilt in 1108 under Pope Paschal II. The entire longitudinal axis of the nave is marked by porphyry rotae bound together. Between the entrance and the choir, a second aisle with circular elements intersects the nave. Once there was a bigger central pattern right in the intersection. For example, the floor of Saint Peter’s nave features a big porphyry rota, where a cardinal and the future emperor prayed during the emperor’s coronation. The choir is enclosed with marble plutei from the lower church dating back to the age of Pope John II (533-535 CE).

Many years passed by before other written evidences of marmorari masters: we can find the name of master Paulus (dating back to 1106) who worked in Ferentino’s cathedral. He is supposedly the author of all the floors and furnishings of the basilicas of San Clemente and of Santi Quattro Coronati, both rebuilt under Pope Paschal II (1099-1118). Also by his workshop is the floor of St. Peter’s Basilica. Master Paulus was the founder of a family of craftsmen; his sons notably realised the ambo in the Basilica of Saint Lawrence outside the Walls in 1148.

The floors of the churches of Sant’Ivo, of San Crisogono, and of Santa Maria in Cosmedin are all credited to their schools. Also belonging to Paulus’ family is Nicola d’Angelo (his grandson), who realised the bell tower of Gaeta’s Cathedral (1148), the altar in Sutri’s Cathedral (1170), and the restoration of the Basilica of St. Bartholomew on the Island in Rome (1180). In the late XII century, Nicola d’Angelo completed his last known work: together with Pietro Vassalletto, he sculpted the Paschal candlestick located in the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls in Rome. A contemporary artist of master Paulus is Drudo da Trivio, whose main work was the ciborium in Ferentino’s Cathedral. He left an inscription there defining himself as civis romanus (Roman citizen), a title which only those who lived and worked in Rome could have. This appellation was especially used by the artists belonging to the Cosmati family, which engraved it in the works realised outside the city of Rome.

From the second half of the XII century to the XIV century, the most active families in the art of working marble were the Cosmatis. Even though Cosmati was the name of just one of the two families (which had Cosma as one of the founders), it was nevertheless used for the whole group of artists; all the works of art similar to that style but realised by other masters are usually defined Cosmatesque.

From the second half of the XII century to the XIV century, the most active families in the art of working marble were the Cosmatis. Even though Cosmati was the name of just one of the two families (which had Cosma as one of the founders), it was nevertheless used for the whole group of artists; all the works of art similar to that style but realised by other masters are usually defined Cosmatesque.

The two branches of the so-called Cosmati were the one of the Tebaldo family, active from the late XII century to the early XIII century, whose founder was Tebaldo himself, and the one of the Mellini family, active from the second half of the XIII century, whose founder was Cosma di Pietro.

The Tebaldo branch is credited with many works, while Lorenzo, the son of the founder, is the author of the decorations of the ambones and the floors in Rome’s Basilica of Santa Maria in Ara Coeli (1185) and of other works outside the city of Rome. His son, Jacopo, notably realised works in Civita Castellana’s Cathedral; together with his own son, Cosma, worked in that cathedral’s portico in 1210.